Former Soldier Reveals Grisly Details of Early Castro Regime Repression at La Cabaña Fortress

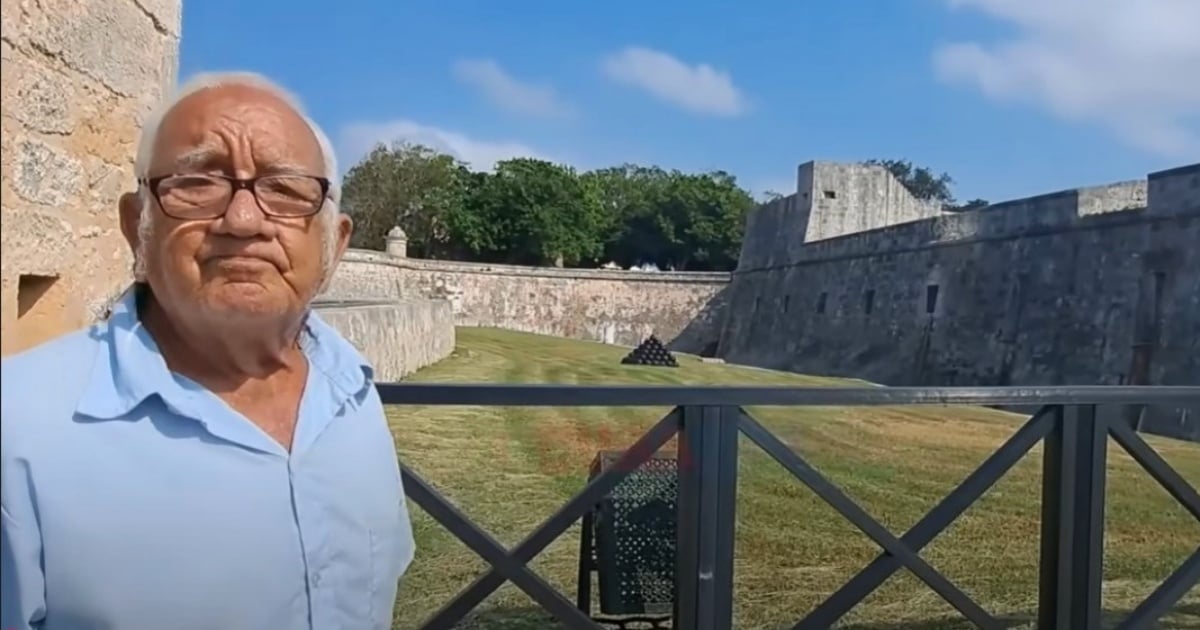

A harrowing firsthand account from Vicente Hernández Brito, a former soldier at the infamous La Cabaña fortress, sheds new light on the systematic brutality that characterized the initial years of the Cuban Revolution.

Vicente Hernández Brito, now 77 years old, has broken decades of silence to detail the chilling procedures surrounding executions carried out under the authority of revolutionary courts. His testimony, recently documented in a report for CubaNet, paints a stark picture of a regime that employed not only overt violence but also calculated psychological torment, and ultimately discarded those who carried it out.

The Mechanics of State-Sponsored Killing

Hernández Brito described a meticulously planned process for carrying out the death sentences. “First bridge with the cage, when we brought the prisoners to take them to the chapel, to take them to execute. There the order was heard: ‘Executive officer, comply with the judgment of the revolutionary court. On behalf of the homeland and the town, proceed.’ Thus the prisoners were shot,” he recalled, conveying a sense of both resignation and enduring trauma.

The executions weren’t simply haphazard acts of violence. Everything, according to Hernández Brito, was “millimetrically calculated.” He explained the presence of a sandbag-protected square post on the second bridge, designed to stop stray bullets. “When they shot someone, the projectile passed it and was splining the stick,” he stated. Reflectors illuminated the execution grounds, typically in the early morning hours, ensuring the sounds of gunfire reverberated throughout the prison, intended to instill fear in the remaining inmates. “The prisoners shouted ‘murderer!’ when they saw that they took someone to the wall,” he added.

Dehumanization and Psychological Torture

Before facing the firing squad, prisoners were subjected to a dehumanizing ritual. They were stripped of all personal belongings, even belts and shoelaces, to prevent suicide attempts. “They took their belt to the prisoners and cords so that they would not hang. From there they were lowered by a ladder where they were shot, down there,” Hernández Brito explained, highlighting the systematic stripping of dignity.

The brutality extended beyond physical violence. Hernández Brito detailed a particularly horrific form of psychological torture known as “El Saladito,” a punishment cell located “under the water tank, where you dropped a head in your head for hours.” He described how prisoners were subjected to a constant drip of water, driving them to the brink of insanity. “Twelve hours there they drove you crazy, but you couldn’t move or turn away the drop. Hence the name. They went crazy,” he said.

From Prison to Tourist Attraction: A Bitter Irony

Today, La Cabaña stands as a tourist attraction, drawing visitors to its historic walls. However, Hernández Brito views this transformation with profound irony. “This place was full of prisoners. Now this is for tourists, but this was ‘bad times since you entered.’ It was a terrible place. Nothing good came here,” he lamented.

The repression, he emphasized, wasn’t limited to those deemed political opponents. Individuals faced imprisonment for minor offenses, such as possessing a small amount of foreign currency. “Do you know how much someone was thrown out for legal membership in currencies? Three years. To another, for having two or three dollars in your pocket, six years for currency traffic.”

Witness to the Death of a Symbol: Pedro Luis Boitel

One of the most poignant moments of Hernández Brito’s testimony centers on the death of Pedro Luis Boitel, a prominent symbol of resistance to Castroism. Hernández Brito recounted being a direct witness to Boitel’s final moments. “I was with a checkpoint that morning and went to bring coffee to the nursing post. And they tell me: ‘The one that is in there is dying.’ I asked: ‘Pedro Luis?’ They told me: ‘Yes, it’s Pedro Luis.’”

He described the profound impact Boitel’s death had on the prisoners. “When he died, I asked the lieutenant for permission to close his eyes. And that was when all the prisoners began to sing the national anthem. They gutting us all. No one could move. No one could leave.” Hernández Brito later learned of the establishment of an International Human Rights Award in Boitel’s honor, a revelation that filled him with pride. “I was very excited. I didn’t know that this recognition existed. I, this old man who is here, is proud to have closed Pedro Luis’s eyes. He died because he was very weak.”

A Forgotten Soldier’s Disillusionment

Hernández Brito’s involvement with the revolutionary government didn’t end with his service at La Cabaña. He later participated as an “internationalist worker,” undergoing military training before being deployed on civil missions, including a stint in Angola.

However, his current reality stands in stark contrast to the promises of the revolution. He now lives in poverty, relying on his daughter’s assistance to survive. “My colleagues and people come and eat from the garbage dumps. This has given a radical change, which is not for what we fight,” he confessed. He questioned the fate of the revolution’s ideals, asking, “Is the health ended or it is not over? Is the guilt of all those things by imperialism?”

Vicente Hernández Brito’s testimony serves as a raw and unsettling window into the inner workings of repression during the early years of Castroism. More than a confession, it is a powerful indictment of a system that justified death “in the name of the homeland and the people,” and then abandoned those who enforced its will. It is a crucial call for historical memory, forcing a reckoning with the foundations of a regime built on fear and ultimately, disillusionment.