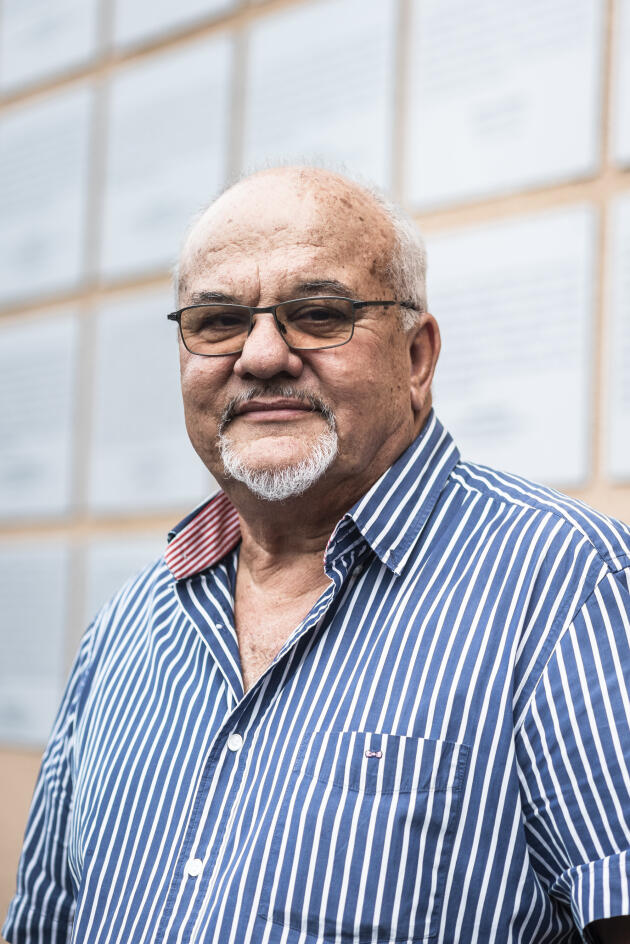

Tears well up in Mayor Patrick Robelin’s eyes. The descendant of convicts evokes his family, “displaced persons from the Jura, subjected to forced labor, then to house arrest, to whose women a few grains of corn were thrown to plant, while the Kanaks were used to quell the fugitives by pitting them against each other, always, always, always…” His town, Bourail, was the first agricultural prison center in New Caledonia.

For a long time, fortunately, in this town of 5,500 inhabitants of the southern province (held by the loyalists), we have been trying to build together, Caledonians, Kanaks, caldoches, mestizos, Arabs. The municipal team works on the common memory. It celebrates the yam, the sacred tuber of the Kanaks. Renames his college after an old local sage, Louis Léopold Djiet. Displays on its walls opening words by Michel Rocard, Jacques Chirac or Nicolas Sarkozy. In Nouméa and Paris, political discussions on the future of Caillou resume between the State, separatists and loyalists. In Bourail, the small municipal team draws on its past for a broader compromise.

The mayor is the first, after three generations of pariahs, to have visited France. He brought his sponsorship to Emmanuel Macron for the presidential election of 2022. “My parents were people who had to scrape by, stay closed in on themselves. They Couldn’t Marry Settler Children Because They Were Straw Hats [nom donné aux bagnards condamnés pour crime et à leurs descendants]. We had to survive. »

Around the table in the meeting room, on this December day, stands Jocelyne Montazi, Kanak, assistant in charge of social affairs. “It is not easy to think together the different legacies of colonization. I took part in the civil war of the 1980s under duress, illuminated every evening like game by armed men while I lived alone, fear in my stomach, in front of others who were just as afraid, as much victims of history as I am. I was ready to die at the time, but I thought, “If we all die, who is going to work for our children?” »

The team also includes Odile Obry, granddaughter of settlers Feillet, named after the governor who, at the beginning of the 20the century, had brought a thousand French people, mostly poor, to populate the island. “My father, a small breeder in Poindimié, is the first Caledonian generation, in this land of suffering. My mother is half Kanak, half Japanese. She waited until she was 80 to find the grave of her own father in Okinawa, deported during the war. I knew the “sale nippone” in primary school. But I lived in the village and in the tribe; by my blood, I am a real world tour, and I feel at home everywhere. »

You have 85.99% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.