He has no brain or heart but he possesses the divine ability to live forever. This tiny creature is called ‘Turritopsis dohrnii’. It is a transparent jellyfish barely seven millimeters long that lives in Mediterranean waters and is the only immortal species of the Earth because it knows how to completely return to a stage of immaturity and be reborn.

The vast majority of living beings, after the reproductive stage, advance in a characteristic aging process whose final destination is death. However, this jellyfish is capable of choosing another path, reversing its life cycle and rejuvenating itself. It does this as if it were a butterfly, but instead of dying when it reaches its most beautiful form, it changes back into a caterpillar. Or it could also be said that it is as if a chicken had the ability to become an egg again, in a Endless cycle that defies the passage of time with rejuvenation.

It is an ‘immortal’ jellyfish, although it is not safe from all threats. It also dies when it becomes the menu of other larger sea creatures. Instead, he walks into eternity if he suffers from any environmental stress. Instead of dying, he transforms and regenerates.

The life cycle of Turritopsis dohrnii

normal life cycle

of the hydroids

stressful environment

post reproductive period

After two weeks it becomes a sexually mature male or female.

A tiny 1mm jellyfish separates from

the tip of the polyp to float in the ocean

The life cycle of

the Turritopsis dohrnii

After two weeks it becomes a sexually mature male or female.

Environment

stressful

Period

postproductive

A tiny 1mm jellyfish separates from

the tip of the polyp to float in the ocean

This amazing ability to circumvent its expiration have made this tiny jellyfish the subject of research. Knowing its biology is not only interesting for marine biologists, but also for those who study human aging who search Nature for clues to find a way to slow down the biological clock.

Carlos López-Otín’s group from the University of Oviedo focused on ‘Turritopsis dohrnii’. His research has now made it possible to unravel the genetic secrets of this strange jellyfish, as well as the general mechanisms that allow its continuous rejuvenation. The details of this work are published in the journal ‘Proceedings’ of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States (PNAS, in its English acronym).

Scientists sequenced the genome of this immortal creature along with that of another jellyfish, very similar, but without such amazing qualities. The most interesting thing was to compare the genomes of these almost sister invertebrates. Thus they were able to identify amplified genes or genes with differential variants that are characteristic of the immortal species.

longevity genes

All these genes affect processes that in humans had already been associated with longevity and healthy aging. They are related to the maintenance of telomeres, the repair and completion of DNA, the renewal of tissue stem cells or the reduction of the oxidative cellular environment.

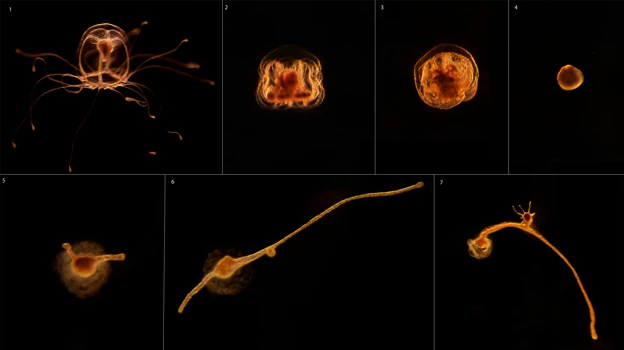

Cycle of transformation in which the immortal jellyfish turns back its biological clock after reaching sexual maturity and is reborn

The research would show that more than there being a single key to rejuvenation and immortality, all these mechanisms would act in a coordinated way, orchestrating the process to guarantee the rebirth of this amazing tiny being.

López-Otín says that this work “does not pursue a dream of human immortality that some announce”, but to understand the keys and the limits of the cellular plasticity. The reason why some organisms are able to travel back in time. “From all this knowledge we hope to find better answers to the many diseases associated with aging that overwhelm us today,” he explains.

The University of Oviedo decided to focus on ‘Turritopsis dohrnii’ after deciphering the genomes of other more complex organisms. Previously, they investigated other champions of longevity, such as the boreal whales that can live 200 years or the giant tortoises of the Galapagos Islands, also centenarians. This previous work allowed them to acquire very important experience to face the study of the unknown jellyfish. The phylogenetic distance between a jellyfish and a human being is large, acknowledges López-Otín, “but it allows us to identify relevant genes that participate in the rejuvenation process and investigate their role and function in humans and in other models.”

From Italy and Japan

Working with this animal model was not easy. María Pascual, an expert in marine ecology, traveled to southern Italy in search of ‘Turritopsis dohrnii’. Other specimens were fished in the waters of the Balearic Islands, near the island of Mallorca and some more arrived from the north of Japan.

The work was hard. This small species was not found on the coast. It was necessary to learn to differentiate their polyps from other similar species. To keep them alive until they reached Asturias, María traveled in a van with the necessary logistics to take care of the jellyfish until they reached the Principality. «There, in the Gijón aquarium, cultivation conditions were established with extreme security measures and attention that were essential for progress on the project and decipher its genome”, recalls the professor of Molecular Biology at the University of Oviedo.

When comparing the genome of ‘Turritopsis’ with its non-immortal sister (‘T. rubra’) no very visible differences were found, until a more human look was put, beyond computer algorithms. The changes are subtle, but they are what explain why only one of these species is a reprogramming laboratory itself and can change to live forever.

It does so at genetic and environmental will. It transforms and becomes more immature when its environment puts it under great stress, although other times it also does so after reproducing, for no apparent reason. Does he decide to be reborn when he begins to age or does he never really age? It is not yet known, says López-Otín. “There is still a lot of research to answer this question. This work is just the starting point.”