Pluto’s quirky climate is actually controlled by a high-altitude haze, not its thin mix of nitrogen and methane, according to fresh data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). This discovery is unique in the solar system.

Pluto’s weather patterns are surprisingly governed by a sophisticated haze layer, a finding that sets it apart from other celestial bodies in the Kuiper Belt.

- Pluto’s weather is driven by a high-altitude haze, not gases.

- JWST data confirmed a hypothesis about haze acting as a thermostat.

- This haze influences climate on other icy bodies and potentially exoplanets.

- The findings offer insights into early Earth’s climate and the origins of life.

“This is unique in the solar system,” said Tanguy Bertrand, an astronomer at the Paris Observatory who led the analysis. His team’s Webb observations reveal Pluto operates a climate system with no clear parallels to other Kuiper Belt worlds.

Faraway Pluto Gets Stranger

Table of Contents

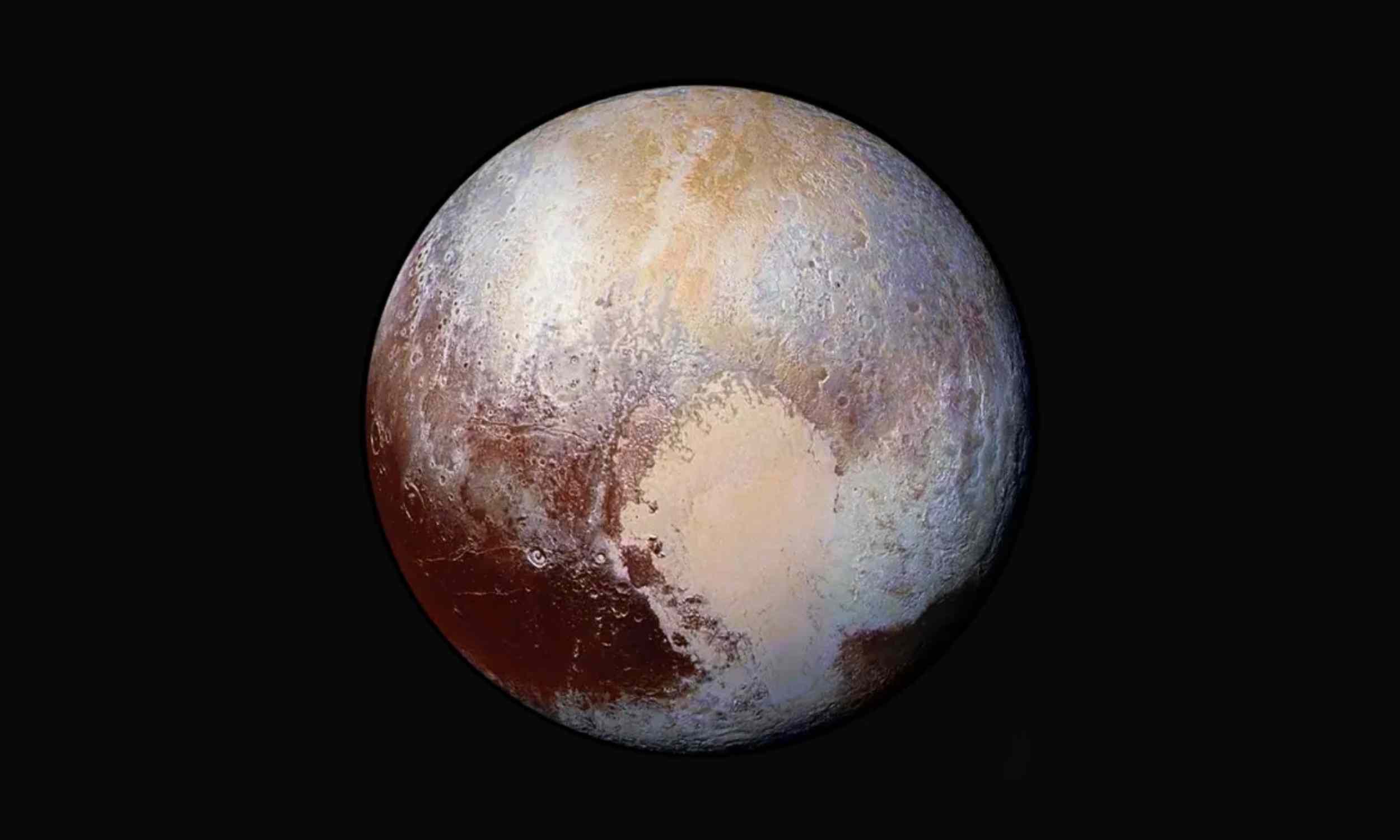

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft provided early clues when it skimmed 7,800 miles over Pluto on July 14, 2015. It spotted vast nitrogen-ice plains, towering water-ice peaks, and the iconic heart-shaped Sputnik Planitia. This flyby proved Pluto is an active world, shattering previous assumptions that it was merely a frozen relic.

The spacecraft also captured images of a striking blue atmospheric shell. This layer extended over 125 miles (200 kilometers) above the surface, organized into at least 20 distinct layers. Such an altitude is remarkable for a body smaller than Earth’s Moon.

Temperature readings from the upper haze layers hovered around -333 degrees Fahrenheit (-202 degrees Celsius). This was about 30 degrees colder than predicted by gas-only models. Researchers suspected that the haze particles themselves were responsible for absorbing heat.

Pluto’s Haze Becomes a Thermostat

In 2017, Xi Zhang proposed a fascinating theory: organic grains formed from methane and nitrogen might absorb sunlight during the day and then release it as infrared energy after sunset. This process, he suggested, could effectively cool Pluto’s sky, challenging the established view that gases alone regulate atmospheric temperatures.

Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument, sensitive to wavelengths from 5 to 28 micrometers, was finally able to test this prediction during a 2022 observing window. Its powerful 21-foot (6.4-meter) mirror precisely separated Pluto’s thermal emissions from those of its moon, Charon. It detected the faint thermal glow indicative of cooling haze.

During the day, these tiny grains soak up solar energy. But at night, they radiate heat so efficiently that the upper atmosphere loses energy faster than it gains it. This cycle, repeating with each rotation of Pluto, acts like an invisible pump, maintaining surprisingly stable, albeit frigid, temperatures.

Splitting Pluto From Its Moon

Before Webb’s advanced capabilities, telescope observations often blurred Pluto and Charon together. This made isolating the subtle haze signal nearly impossible. With its significantly higher resolution, Bertrand’s group could measure separate light curves at specific infrared wavelengths (15, 18, 21, and 25 micrometers).

These measurements precisely traced the extra emission directly to Pluto. Spectral analysis revealed that the grains resemble Titan-style tholins, which are complex organic molecules. They are coated in thin films of hydrocarbon and nitrile ice. Though these particles weigh almost nothing individually, their vast collective surface area overwhelms the cooling influence of any gas molecule.

Charon’s light curve, in contrast, matched that of a bare icy crust. This confirmed that its companion lacks an atmosphere substantial enough to interfere with the readings. By effectively removing Charon’s contribution, the team finally settled a debate that had persisted since the New Horizons mission returned its initial thermal maps.

Hazy Worlds Other Than Pluto

Bertrand noted that other celestial bodies, like Neptune’s moon Triton and Saturn’s moon Titan, also possess photochemical hazes. These worlds might rely on similar haze-driven thermostat mechanisms. If future Webb observations detect comparable thermal glows on these bodies, scientists may need to revise atmospheric models across the board.

Exoplanet surveys have already identified opaque hazes on mini-Neptunes and super-Earths. Lessons learned from Pluto’s haze could therefore be crucial for decoding the climates of alien worlds. Accurate temperature estimates are vital for identifying habitable zones and directing valuable telescope time.

Closer to home, an upcoming Webb mission is scheduled to observe Triton late next year. The goal is to search for similar mid-infrared excesses. A positive detection would strongly suggest that tiny particulate matter plays a dominant role in the energy balance of icy bodies throughout the solar system.

What It Means for Early Earth

Climate models of the Archean Earth suggest that a methane-rich haze might have enveloped the young planet. This haze could have scattered sunlight, moderating surface temperatures during a period when the Sun was significantly fainter. Pluto offers a living analogue, demonstrating how sparse organic aerosols can still regulate heat flow.

By calibrating their models with Webb’s data, geochemists can refine estimates for early Earth’s surface temperature and its protection from ultraviolet radiation. These adjustments have significant implications for theories about where and when the first biological molecules remained stable enough to form life.

Organic hazes absorb ultraviolet light, which can slow the breakdown of fragile molecules like ammonia. This potentially created a more hospitable surface environment for nascent metabolisms. Pluto’s haze data provide a crucial reality check on the thickness required for such atmospheric blankets to transition from warming to cooling effects.

Future Questions

Pluto orbits the Sun once every 248 Earth years. This means JWST’s snapshots in 2022 and 2025 capture only the early phases of a prolonged arctic winter at its north pole. Scientists anticipate the haze thermostat will become even more critical as the Sun’s influence diminishes further.

Webb is well-positioned to test this forecast over the next decade. Meanwhile, researchers on Earth are recreating Pluto’s conditions in laboratory chambers, freezing methane-nitrogen mixtures to replicate the unusual grains and measure their radiative properties. This methodical approach is transforming a visually striking blue glow into a fundamental example of atmospheric physics.

Why This Matters for Climate Science

General circulation models that incorporate aerosol physics already indicate that fine particles can significantly alter global temperatures on young, Earth-like planets. Pluto now serves as the first natural, real-world benchmark for these calculations, extending beyond laboratory experiments.

The influence of aerosol feedbacks also impacts proposals for geoengineering, cloud microphysics, and the interpretation of data from exoplanet observations. With Webb’s detailed detections, modelers can improve the accuracy of their predictions. Policymakers can also better assess the planetary-scale consequences of even minuscule floating particles.

This haze-driven cooling principle could potentially moderate supercritical atmospheres on distant mini-Neptunes. This suggests that some planets previously deemed too hot might actually harbor temperate cloud decks. Future space telescopes will likely search for the thermal signatures of these unseen aerosols when identifying promising targets for life detection.

The study is published in Nature Astronomy.