2024-11-05 05:58:00

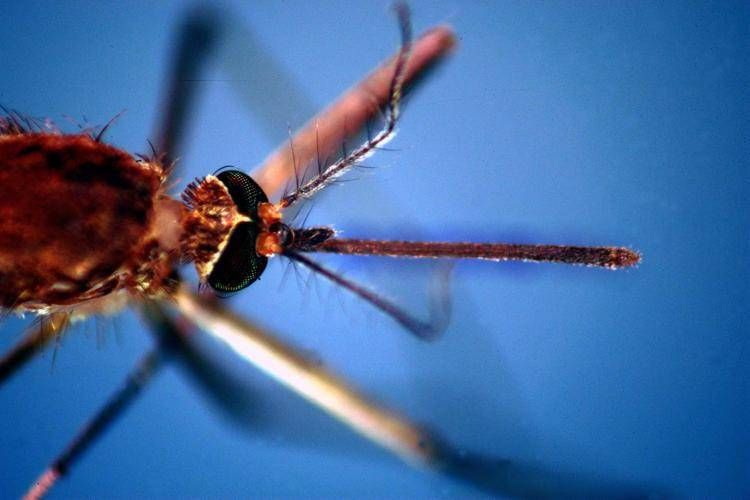

among the ‘good bacteria’ in their intestines there is one that could inadvertently ’betray’ them, playing in favor of the mission of controlling these disease-carrying insects. <a href="https://time.news/addressing-the-dengue-fever-crisis-in-thailand-pesticides-vaccinations-and-community-efforts/” title=”Addressing the Dengue Fever Crisis in Thailand: Pesticides, Vaccinations, and Community Efforts”>Aedes aegypti in particular has come under the lens of scientists, on whose wings Dengue ‘flies’, but also yellow fever and the Zika virus. A new study published in the ‘Journal of Applied Microbiology’ could launch an assist to global health programs that, to stem the spread of these infections, focus on the release of male mosquitoes that are sterile or that prevent the transmission of diseases. The ‘infiltrator’ that could lend a hand is the Asaia bacterium: according to experts it is capable of accelerating the development time of larvae by a day, which could give impetus to mass breeding projects that must produce millions of adults . These programs, the researchers note, can be significantly more effective than widespread spraying of insecticides, as mosquitoes have developed resistance to many commonly used chemicals.

What’s in the studio

The new study, led by the universities of Exeter (UK) and Wageningen (Netherlands), examined how the Asaia bacterium influences the development of mosquito larvae. “We know that every species, including humans, depends on a microbiome, a complex mix of microorganisms that live inside the body,” highlights Ben Raymond, professor at the Center for Ecology and Conservation at the university’s Penryn Campus of Exeter in Cornwall. “Asaia bacteria are thought to be beneficial parts of the mosquito microbiome, but this has never been rigorously tested in Aedes aegypti.” What is known is that “Aedes aegypti mosquito larvae cannot develop without a microbiome – continues the expert – and the study shows that two Asaia species can play a beneficial role”. The larval period of the Aedes aegypti mosquito usually lasts around 10 days, so speeding up by one day could provide a valuable boost to the mass production of disease-fighting male mosquitoes.

The scientists thought of adding Asaia bacteria to the water in which the mosquito larvae developed. And they observed two species actually had the effect of speeding up development. The mechanism is unclear, but these bacteria do not appear to have provided direct nutritional benefits. Instead, they appear to have changed the broader bacterial community, reducing the abundance of some microorganisms, including some species that may be slightly parasitic. The Asaia bacteria also remove oxygen, creating conditions that produce the hormones needed to promote growth.

Interview between Time.news Editor and Dr. Elena Barone, Microbiologist Specializing in Mosquito Borne Diseases

Editor: Good morning, Dr. Barone, and thank you for joining us today. Your recent research published in the Journal of Applied Microbiology sheds light on a potentially revolutionary approach to controlling mosquito populations. Can you tell us about the role of the Asaia bacterium in this context?

Dr. Barone: Good morning! Yes, the Asaia bacterium is quite fascinating. It’s a naturally occurring bacterium found in the intestines of various insects, including mosquitoes. Our study suggests that it could play a critical role in mosquito control by enhancing the larvae development rate. Essentially, it speeds up their lifecycle, which can be leveraged to produce billions of sterile male mosquitoes for release into the wild.

Editor: That sounds promising. How does the acceleration of the larvae’s development translate into practical applications for mosquito control programs?

Dr. Barone: By shortening the development time of larvae by a day, we can significantly increase the number of adult mosquitoes produced in breeding facilities. This can be crucial for initiatives like the Sterile Insect Technique, where releasing sterile males into the wild can drastically reduce the populations of disease-carrying females. It aids in rapid scaling of production, which is essential for mass release programs.

Editor: We’ve seen conventional methods of pest control, like widespread insecticide spraying, becoming less effective due to mosquito resistance. How does your method compare in terms of efficiency and environmental impact?

Dr. Barone: That’s an excellent question. Our approach primarily focuses on biological control rather than chemical means. Studies indicate that breeding and releasing sterile males, particularly those bred with the help of Asaia, can be significantly more effective and sustainable than conventional spraying. Moreover, it minimizes the environmental footprint and reduces the risk of harming non-target species.

Editor: With rising concerns over diseases like dengue and Zika virus, how urgently is your research needed? Are global health programs showing interest?

Dr. Barone: The urgency is real. Diseases like dengue, yellow fever, and Zika continue to pose severe public health challenges, especially in tropical and subtropical regions. Several global health programs have expressed interest in our findings, as they seek innovative solutions to curb outbreaks and improve community health resilience.

Editor: What are the next steps for your team after this groundbreaking study? Are you conducting field trials?

Dr. Barone: Yes, field trials are indeed the next step. We are currently in discussions with partner organizations to implement pilot projects. The goal is to monitor and evaluate how effectively the Asaia-enhanced breeding strategy impacts wild mosquito populations and disease transmission rates.

Editor: Exciting times ahead! As a final thought, what message would you like to leave our readers regarding the interplay between microbiology and public health?

Dr. Barone: I’d like to emphasize that understanding and navigating the ecosystems of microorganisms can offer us innovative tools in the fight against emerging diseases. Collaboration between scientists, public health officials, and communities is crucial to harness these insights effectively. Together, we can create healthier environments and combat these persistent threats.

Editor: Thank you for these insights, Dr. Barone. It’s reassuring to see science paving the way for solutions to global health challenges. We look forward to hearing more about your progress!

Dr. Barone: Thank you for having me! It’s a pleasure to share this important work with your audience.