Sometime in 1980, music producer Manfred Eicher was listening to the radio on his way from Stuttgart to Zurich. He was so intrigued by what they were playing that he turned off the highway and stopped on the nearest hill. Then time seemed to stop. And in that rare moment, in Eicher’s words filled with “angelic music,” the seed of a fateful collaboration sparkled.

The composition Tabula rasa was composed by Estonian native Arvo Pärt with hermit appearance several years before he emigrated from the then Eastern Bloc to Vienna. Four years after the highway revelation, Eicher’s record company ECM released a profile album named after this composition.

The soft colors and minimalistic design of the breakthrough record foreshadowed the synergy that continues to this day between the unique label and the shy artist. He will celebrate his ninetieth birthday in September 2025. Even before that, on May 19 at the Rudolfinum, his emotional works will be performed at the Prague Spring Festival by another longtime ECM collaborator, conductor and choirmaster Tõnu Kaljuste, with the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir.

The Munich publishing house made not only Pärt, but also minimalist Steve Reich, unclassifiable pianist Keith Jarrett and saxophonist Jan Garbark more widely known. It has always understood contemporary music broadly and loosely, for example combining contemporary and medieval music. Eicher seeks authors who take risks. And publishes them under the overarching motto “The most beautiful sound right after silence”.

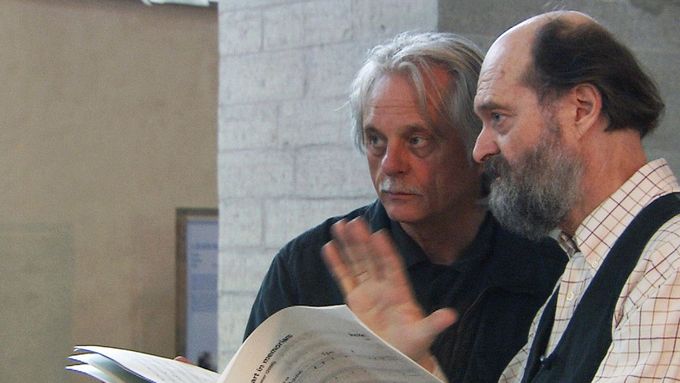

He and Pärt agree on that. “Silence is nothing to me, out of which God made the world. Ideally, silence is something sacred. If you turn to it with love, maybe it will result in the awakening of music,” once said a deeply religious author. He became friends with the producer over the years. This is shown, for example, by asking him to dance in the middle of a rehearsal of a composition for orchestra and choir, as captured in the 2009 documentary film Sounds and Silence.

Cleric and janitor

Thanks to ECM, Arvo Pärt became a global phenomenon in the 1980s and later became one of the most performed living composers. According to music critic Paul Griffiths, the label’s creative atmosphere and background allowed him to fully focus on his own path.

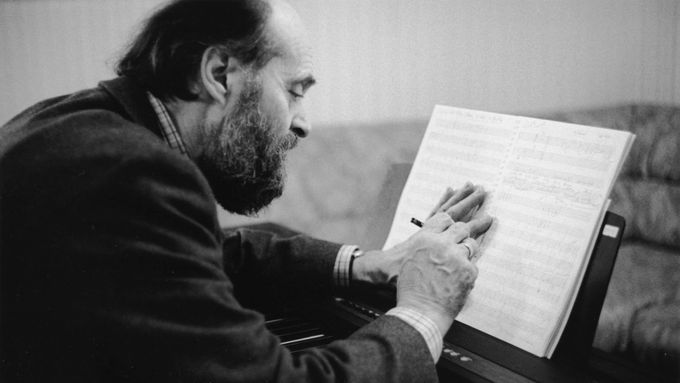

Arvo Pärt will celebrate his ninetieth birthday next year. | Photo: Kaupo Kikkas / Arvo Pärt Centre

While he was composing, ECM defined his image as the evangelist of spiritual contemporary music. A composer from a post-Soviet country with the visage of an Orthodox monk, who named his technique with the magical word tintinnabuli, aroused people’s curiosity. He began to be referred to as a “sacred minimalist” standing outside time and trends. His slow-flowing, visceral music, far removed from the mundane volatile reality, offers solace and space for recollection.

Orthodox visage is not accidental. Pärt converted from Protestantism to Orthodoxy in the early 1970s, at a time of creative crisis and intense search for himself. Until then, he had undergone a dynamic development not unlike many of his peers. Neoclassicism was replaced by dodecaphony, strict seriality and collage technique. At the same time, faith resonated more and more powerfully in him.

A sharp turn was heralded by 1968’s Credo, a composition combining aggressive dissonances with simple harmonies. But the name alone bothered the Soviet authorities, who banned it in Estonia.

The adversity of the repressive regime met with personal impasse, so Pärt went silent for a while. He earned his living on the radio, in the evenings he studied Gregorian chant, medieval and renaissance music.

New insights are reflected in his Third Symphony from 1971, somewhere halfway between the old and new styles. Existential distress must have weighed on the author with an unprecedented intensity.

He asked the question of what to do next to the clergy and the janitor, whom he saw sweeping the sidewalk in front of the house one morning on his way to work. “How do you think a composer should write music?” he asked him. After the initial shock, the janitor replied, “I think he should love every sound.”

The long creative hiatus culminated in 1976, when the short piece for piano Für Alina was performed at a concert. There are few notes in it, the score is only two pages long. The two melodic lines intertwine and pass each other like old friends in a peaceful conversation. Was it a stunning comeback? Those words usually evoke something spectacular, but in the case of the “sacred minimalist”, bombast has been replaced by asceticism. Not strict, rather humble and loving. The composer took the janitor’s advice to heart.

Since then, Pärt’s style has understandably continued to evolve. He watered down the originally clear rules, but the overall spiritual orientation and generally greater emphasis on liturgical and choral music remained with him.

In the documentary Sounds and Silence, composer Arvo Pärt asked ECM producer Manfred Eicher to dance. | Video: ECM Records

The Baltics in Prague

Pärt was initially promoted by other notable artists from the Baltics: the Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer or the conductors Neeme Järvi and Andres Mustonen with their ensemble Hortus Musicus, originally specialized in early music.

Järvi performed the composer’s Second Symphony at the Prague Spring Festival in 1975, which is defined by ironic work with musical collage. Four years later, Kremer played the now famous composition Spiegel im Spiegel, then barely a year old, in the Czechoslovak capital. In 2006, Hortus Musicus performed works from anonymous authors from the 12th century to Pärt.

Pärt’s compositions at Prague Spring will be performed by the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, led by Tõna Kaljuste (pictured). | Photo: Kaupo Kikkas

Next year they will be joined by Tõnu Kaljuste with the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir. An energetic conductor and choirmaster, he founded it in 1981, even before establishing cooperation with Pärt at the end of the decade. Manfred Eicher soon heard about her and invited the Estonian to the ECM label, for which Kaljuste has since recorded 19 albums. In addition to Pärt, other compatriots, such as Velja Tormis, Erkki‑Sven Tüür or Tõnua Kõrvits, interpret on them.

Kaljuste won a Grammy Award for his work on the 2009 album Adam’s Lament, featuring eight of Pärt’s choral compositions. It is also signed under recordings of his instrumental works, including all four symphonies. They can be used to illustrate the path taken by the composer.

“Each of the four symphonies is characteristic of one creative period,” describes Kaljuste. “Their set can be understood as a great symphony of a generation, as it reflects the search of many of those who took their first creative steps in the 1960s.”

Kaljuste and the award-winning ensemble will perform a dozen of Pärt’s choral works in Prague. The oldest is the Summa from 1977, one of the first in his refined tintinnabuli style. The longest, the Berlin Mass, premiered in the German capital a few months after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Most of the others date from the turn of the millennium. In the same way, the people of Prague will hear a piece of Pärt’s most extensive work called Kanon Pokajanen, directly dedicated to Kaljuste and his choir. Part of the extensive cycle is also the catchy composition Prayer After the Canon, which is closer to historical liturgical chants than to contemporary music.

According to the authors of the Cambridge guide to Pärt’s work, the rational system woven into the tintinnabuli style was never a goal, but a means to achieve beautiful new sounds. “I believe,” Pärt’s wife Nora once summed up, “that Arvo’s music means more to the ears than to the intellect.”

Video: Sample from the Canon of Repentance by Arvo Pärt

The people of Prague will also hear a part of Arvo Pärt’s most extensive work, called in translation the Canon of Repentance. It was recorded by the choir Cappella Amsterdam. Photo: Roberto Masotti | Video: Harmonia mundi