2024-02-15 14:12:00

Javier Segura del Pozo, health doctor

We continue our exploration of health care in the 18th century that we began last week with “The Birth of Public Health.” Today we will see how in health research in Baroque Spain, “medical pluralism”that is, the “promiscuous” consultation of different health professionals: from relatives and neighbors, with their home remedies, to healers, herbalists, magicians, clerics, barbers and academic doctors, or the use of votive offerings, offerings, processions, etc. . heal. There have been peculiar cases of hybridization of cultures and knowledge (popular medicine/scientific medicine) with “polyphonic” practices, such as that of the new Spanish healers.

Medical pluralism

Although medical guilds increased their ability to control healthcare practice throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, academic physicians by no means monopolized the market or dominated it. According to Lindemann, the boundaries between orthodox and heterodox medicine, between elite medicine and popular medicine, have always been flexible. People sought each other’s services. This “promiscuity” has been called “medical pluralism” and it extended to all social classes (in this sense, it is not true that the privileged classes consumed academic medicine and the popular classes only popular medicine).

Medical practice almost always began at home with folk remedies. From there he went on to ask advice from relatives or neighbors (for example, women who fixed dislocated bones), to end up consulting the most diverse healers: male and female healers, herbalists, priest-doctors, bath doctors (medical hydrology) , academically trained doctors or “specialists”, such as lithothymists (removal of stones from the urinary tract), bone doctors, ophthalmologists or tooth removers. They could also turn to clerics, exorcists, magicians or witches and use votive offerings, offerings, prayers, processions. The norm was simultaneous and successive queries[1].

Women were still the primary providers of health care in the 18th century, especially in rural areas. As family caregivers, neighbors or healers, they possessed the traditional knowledge of folk medicine, although they also applied remedies shared by academic medicine (reserved for men), such as bloodletting. Image: “The Bleeding,” painting by Quirijn van Brekelenkam (fl. 1648–1669) from the mid-17th century.

This medical pluralism is confirmed in several texts that specifically refer to the healthcare practices of the Hispanic monarchy in the modern age. In Carolin Schmitz’s review of the picaresque work Life and facts of Estebanillo González (1646)[2], With numerous allusions to medicine and disease in the 17th century from the perspective of a Spanish golden age thief, the many and varied actors and actresses practicing regulated and unregulated medical professions are listed: a) barbers-surgeonsthat to practice legally, they had to first assist and serve a teacher for a few years, and then agree not to charge the poor in exchange for using them for teaching; B) charlatans or motambancos: street vendors selling exotic homemade medicines to the public in the context of a street drama; c) use of holy healersto whom miraculous healings are attributed; D) academic medicinewho however often had a negative and derogatory image, because they were considered incompetent, arrogant, greedy and corrupt professionals; AND) home medicinein which women have a special role, based on the knowledge of home remedies inherited from generations.

Cover of the picaresque work Life and events of Estebanillo González (1646), which contains numerous allusions to medicine and THE disease in the 17th century. From the perspective of a Spanish Golden Age thief, the many and varied actors and actresses practicing regulated and unregulated medical professions are listed.

Cover of the picaresque work Life and events of Estebanillo González (1646), which contains numerous allusions to medicine and THE disease in the 17th century. From the perspective of a Spanish Golden Age thief, the many and varied actors and actresses practicing regulated and unregulated medical professions are listed. According to this novel, the patients They had a more active attitude than one might expect: they created demand and influenced the therapeutic process, changing health workers, professional or lay, depending on the type of pathology and depending on the outcome. The novel also reflects how an assimilation, reception and appropriation of medical knowledge occurs at a popular level, which then adapts to the standards of Galenism.

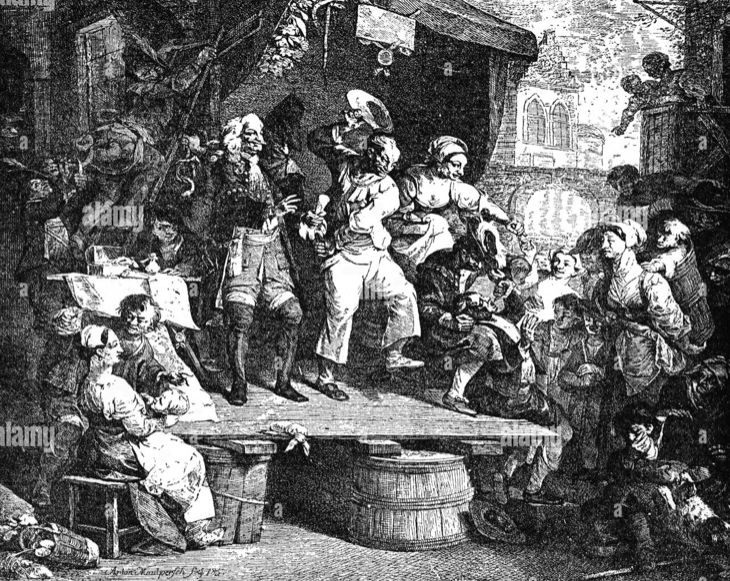

In the context of medical pluralism, the charlatans or motambancos They were other health workers: they were street vendors of homemade medicines, with exotic connotations, which they offered to the public in the context of a street drama. Charlatans on stage, copper engraving by Franz Anton Maulbertsch (1724 – 1796), Germanisches Nationalmuseum.

In the context of medical pluralism, the charlatans or motambancos They were other health workers: they were street vendors of homemade medicines, with exotic connotations, which they offered to the public in the context of a street drama. Charlatans on stage, copper engraving by Franz Anton Maulbertsch (1724 – 1796), Germanisches Nationalmuseum.The new Spanish healers

In this sense, Estela Roselló describes how healers in 17th-century New Spain adopted particular negotiation strategies to survive in a world of male supremacy. These strategies were based on a process of cultural hybridization and knowledge:

«These women, sometimes indigenous, sometimes Spanish, other mulatto or mestizo, were called by both men and women, by people from the most disadvantaged strata and by people from the most privileged classes (…) [y lograron] “create your place in the universe of medical pluralism of New Spain”[3].

In Hispanic America the healers has dominated healthcare through a process of cultural and knowledge hybridization, having the doctors of academic education a very limited presence in those Indian kingdoms of the Hispanic monarchy. Image: “Mulatto”, “mestizo” and “quarterón”, according to an 18th century “caste table”. Author unknown.

In Hispanic America the healers has dominated healthcare through a process of cultural and knowledge hybridization, having the doctors of academic education a very limited presence in those Indian kingdoms of the Hispanic monarchy. Image: “Mulatto”, “mestizo” and “quarterón”, according to an 18th century “caste table”. Author unknown.This world was so specific that it could hardly be threatened by a predominantly male academic medicine, which in both the 17th and 18th centuries had a very limited presence in the places where the social majority lived:

«Certainly the healers of the American viceroyalty did not form a guild or guild that identified them by their medical work; However, in everyday life, New Spain society recognized that healers were women with a particular identity. Not only that; Furthermore, society at large accepted that the knowledge of healers belonged only to them and to no one else. It was undoubtedly a feminine knowledge and, in this sense, a mysterious, hidden knowledge, surrounded by an aura of magical and irrational power.[4].

This idea was anchored in pre-Hispanic times, when Mesoamerican societies had Titica (healers) endowed with recognized supernatural powers, who dedicated themselves to medical matters. And where there was no clear separation between magical and non-magical (and therefore these subjects were generically considered “sorcerers” and “sorceresses”). Although many of them were viewed with suspicion by the inquisitorial authorities, “beginning in the 16th century, healers had made themselves noticed on the scene of viceregal medical practice and had had no qualms about living and interacting with the Spanish doctors who” did their work in the first hospitals of the evangelizing missionaries.” [5].

The author also shares the idea that, at least in the 16th and 17th centuries, there was no clear opposition between popular medicine and scientific medicine. The medical knowledge of healers focused not only on restoring physical balance and restoring harmony in the patient’s body, but also on holistically restoring social balance. They were particularly appreciated for their intervention on certain diseases or for their specialization in certain techniques, recognized by the academic world itself. For example, only healers could heal “Women’s Disorders”attributed to the realm of the emotional and magical. And among their many tasks, they attended births, used their knowledge of local herbalism to produce medicines, and used certain procedures, both pre-Hispanic and European: purges to remove foreign bodies from the body (spiders, worms, stones, etc.); healing through touch; trampling on the sick; apply oils and ointments; using images of saints, virgins and miraculous Christs, carrying out bloodletting (which converged with the indigenous tradition of sacrificial and religious punctures); or cleaning and dressing patients[6]. The healers therefore practiced “hybrid” and “polyphonic” medical knowledge, understandable to the majority of the inhabitants of New Spain and which were part of the common sense of this society.[7].

[1] LINDEMAN, M. (2002). Medicine and society in modern Europe, 1500-1800. Madrid: Siglo XXI Editores, p. 226.

[2] SCHMITZ, C. (2016). “Barbers, charlatans and sick people: the medical plurality of baroque Spain perceived by the rogue Estebanillo González”, Dynamic36 (I), pp. 148-165.

[3] ROSELLÓ, E. (2018). “The Medical Knowledge of the Healers of New Spain: A Female Niche in the Medical Pluralism of the Spanish Empire.” Historical studies, modern history40, no. 2, page. 182.

[4] IbidP. 182.

[5] Ibidpp. 185-186.

[6] Ibidpp. 187-193.

[7] IbidP. 195

#Medical #pluralism #Public #health #doubts

The text discusses the interplay between traditional healers and the academic medical profession in 17th and 18th century New Spain (present-day Mexico). The healers, often women from diverse backgrounds (indigenous, Spanish, mestizo), developed unique strategies to navigate a male-dominated medical landscape. These women played a critical role in the healthcare system, often being the primary source of medical care for most people.

Key Points:

- Cultural Hybridization: The healers created a space for themselves within a culturally hybrid medical system, combining indigenous knowledge and practices with European medical concepts. This allowed them to be accepted by various societal classes, making their services vital in both urban and rural settings.

- Feminine Knowledge: The knowledge of these healers was considered feminine and mysterious, often associated with spiritual or supernatural powers. Their expertise was widely recognized in society, even if they didn’t form formal guilds.

- Historical Context: The role of healers can be traced back to pre-Hispanic societies where medical practitioners (Titica) held acknowledged healing abilities within communities. This historical background portrayed them as integral to the social fabric, blurring the lines between magical and medical practices.

- No Clear Division: The tension between popular medicine and academic medicine was less pronounced in this era. Healers addressed not only physical ailments but also emotional ones, focusing on restoring social and individual harmony.

- Specific Expertise: Healers specialized in areas often deemed unsuitable for academic doctors, like childbirth and women’s disorders. They utilized a blend of herbal remedies, physical touch techniques, and ritualistic practices, which resonated more with the local population.

- Acceptance vs. Suspicion: While the inquisitorial authorities viewed healers with suspicion, their interactions with Spanish doctors showed a complex relationship where both realms of medicine existed concurrently.

the text illustrates how healers in colonial New Spain navigated a hybrid medical landscape, asserting their identity and importance within a society grappling with cultural and medical plurality. Their practices were vital not only for individual health but for maintaining the broader social equilibrium.