2024-03-27 12:23:02

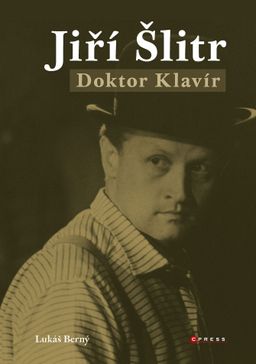

In those 100 years, the world has changed and society has forgotten many things that moved it. Fortunately, not for the hitmaker and co-founder of the Semafor Theater Jiří Šlitra, who was born just a century ago. The most comprehensive Šlitra monograph written by radio editor Lukáš Berný reminds him of him. It came out recently, it’s called Doctor Piano.

Miroslav Horníček teased his friend Šlitra that the native of Zálesní Lhoty, a village in the foothills of the Giant Mountains, lived like Tarzan for the first few years and that the mayor of his village went crazy with terror when he first saw the car.

The method of showing mutual sympathy by means of mild insults also entered Šlitr’s repertoire in a pair with Jiří Suchý; it was Horníček who introduced the two. Šlitr studied law, but devoted himself mainly to painting and music, while significantly transforming Czech songwriting.

An awkward introvert who, even before the foundation of Semafor, could not even approach the instrument in a relaxed manner during the Laterna Magika performance, and therefore was dragged onto the stage already sitting with a piano, found his stage persona on stage and became a popular comedian. At the height of his creative ambitions, he died as a result of gas poisoning on Štěpán in 1969, he was 45 years old. His melodies such as Klokočí, Ah, ta láska neskéka, Tereza and Purpura are still sung today.

Doctor Klavír, as the new book is called, was originally a character from a nonsense story by the actor Josef Hlinomaza. Miroslav Horníček borrowed it for the memory of Šlitra for the anthology, which was published a year after his death. The author of the new publication, Lukáš Berný, was not inventive in this regard, just like when he repeats known facts from commonly available literature in the text.

However, it would be too late to criticize Berné – critics of the time similarly resented Šlitra for looking too much at Western musical patterns, perhaps with the unspoken hope that he would prefer to compose polkas or parts.

Jiří Šlitr and Jiří Suchý with a gramophone record in Šlitr’s studio in Prague’s Vinohrady, 1965. | Photo: CTK

In addition, Berný really collected a number of new facts, for example Šlitr’s mother’s diary, and in addition to an honest study of archival materials, he talked to a lot of eyewitnesses. He proceeded sensitively. When, for example, he tries to build a portrait of Šlitra as a person, he does not force his partner, the actress Sylva Daníčková, to go to any lengths. He respects her privacy and focuses on the essentials.

So what was Šlitr like? Shy yet ambitious, somewhat cold and at the same time surrounded by many friends and women. He conquered Czechoslovakia, but his ambition was to shine on New York’s Broadway.

Among the strongest passages of the book is the breakdown of how the cosmopolitan Šlitra became a patriot after the August occupation in 1968. How the soloist, for whom Jiří Suchý was only the closest professional colleague for a long time, found a friend in this other Jiří. Šlitr, a man endowed with many talents and at the same time with a kind of non-socialist diligence, was full of contradictions. Berný does not cut corners and often sees in them an engine that drives the protagonist’s ambitions further than the horizon of Wenceslas Square, which was enough for many of his colleagues at the time.

The book was published by the CPress publishing house from the Albatros Media group. If any reserves can be found, it is precisely in the publisher’s approach. The editing is sloppy in places, so in the caption of one photo – Berný collected a respectable number of them, as well as hitherto unknown facsimiles – for example, we read that Šlitr’s first love subsequently became a “doctor of veins and blood vessels”.

The graphics did not deal with the amount of visual material on the large A4 format very inventively, remaining straddling somewhere between the aesthetics of the 60s and 90s of the last century. The promotion of the work focuses more on the tempting marginalia – see the bed picture of a dressed Šlitar with a stripped-down Naďa Urbanková and Věra Křesadlová on the back cover. All this somewhat levels Berné’s remarkable text and his research efforts.

The Semaphore celebrations do not end, in September the music critic Pavel Klusák will publish a book called Suchý and Šlitr, Semaphore 1959-1969. It is supposed to be a comprehensive guide to their work from Reduta to Šlitr’s death. “At the same time, it is an attempt to interpret all of this,” promises Klusák.

Doctor Klavír focuses primarily on personal and cultural-social connections, all over a longer period of time. Both publications can thus be suitably complemented and build a truly layered portrait of a personality who co-determined the cultural ferment of the 1960s.

Lukáš Berný: Jiří Šlitr – Doctor Piano

Publishing house CPress 2024, 699 crowns, 168 pages